-I started for completely personal reasons. Basically I thought it was a cool thing to try. I also thought that learning a few party tricks would make up for what I thought was my lack of social ability and personality.

-I was training long before I knew any kind of money or career could come from it. It was always about personal development.

There was even a point where I told a friend I didn't think it was a good idea to try to become a professional stuntman because there are too many unknowns and risks involved. Not only did I not know a career could be made from it, I actually believed it was not possible. I was wrong.

-I was not sedentary, but by no means athletic as a child. I really didn't do much in my childhood that prepared me for the kind of training I currently do.

-I started teaching not long after starting to train seriously. Again this was for mainly selfish reasons.

Basically I just wanted some people to train with and to create a community of sorts. I tried to cultivate interest by teaching people to get them interested.

Also since I had very limited feedback or reference material in my own training, teaching others was a way to access a different learning process. This helped to eventually understand the techniques to a greater depth.

Basically, teaching is a completely separate skill compared to training, performing or completing as an athlete. It does not come natural and needs to be developed over time like anything else. Teaching people early on gave me an advantage for what I do now.

I like to explain it like this:

"Teaching is about getting into someone else's head in order to get them out of theirs."

-I am self-taught. Most of my progress in the first few years was made through a vague knowledge of possibilities combined with obsession, dedication and experimentation. I was stubborn and in reality not a very good student.

I had somewhat of a scientific experimental method to training, but sometimes science is more art than science.

It took me about 5 years into training to learn how to embrace criticism.

I used to have a sizable ego and had to learn the hard way that I wasn't as good as I thought.

-When I say I'm self taught that doesn't mean I didn't learn from anyone, quite the opposite. I learned from countless people directly and indirectly. All these people influenced my style, but nobody formally trained me in anything on a regular basis.

I learned everything the worst way possible, and had to go back to fix it after all the bad habits were built up.

-I also spent about 5 years teaching kids gymnastics and cheerleading, both recreational and competitive. The learning process of a child is completely different to that of an adult, and it is very important to understand this difference. Adolescents have their own individual learning styles as well.

Having exposure to all of this helps greatly to be able to modify my teaching style on the spot. I still enjoy working with the younger generations. The main reasons I quit were the high energy cost of the work, the low pay, and most important having to work for superiors whose approach I did not agree with.

The advantage of this line of work is that I got to stay close to what I was passionate about and still had some free time to pursue my interests.

-I do not consider myself well-read. I never really found reading that helpful for skill learning. Too much theory and not enough practice. It's not difficult to be well versed in theory; absorption and regurgitation of information was my specialty in school. Too many people know how to make it sound like they know what they're talking about when they haven't gone through the process themselves.

I'm not undermining the benefits of reading, but there needs to be an even ratio between reading and doing.

When I read about something that interests me, I immediately go out and try it. Until you understand how concepts apply to the real world, the theory is just that.

-I went to school and got a Bachelor's Degree in Physics with minor in math. I basically picked it on a whim after being undecided in Major for my first year.

It's not something I was super passionate about but it sounded cool. I wouldn't say I use a lot of it now, but the development of the analytical mindset definitely helped.

Out of college, I got a job related to my field doing quality and environmental testing on massive radiation detectors.

-I have no letters after my name, no certifications and I hold no value in pieces of paper. Feel free to call me uneducated in that regard, I just don't care for formalities.

I do hold value in someone's name, reputation, and ability. No piece of paper or fancy acronym can accurately represent that.

This is what I do and this is what I can do. Let my name act as my resume.

-My business title is my name; the one that I was born with(and made fun of for in my younger years). After moving to the US as a child, I used to hate not having a "normal" name but now I embrace it.

Rather than having a flashy or catchy title, I prefer to put my name and reputation on the line. I let my own name represent me.

-I have done my research in different methods. Most teachers have one narrow method of teaching a skill, which is not a bad thing at all.

I however, prefer to research as many different options as possible of reaching the same goal. This is why I spent time studying martial arts, gymnastics, various forms of weightlifting, dance, circus, etc. Not only do you get to see the options, but it gives a better view of what limitations people of different backgrounds have when learning different skills.

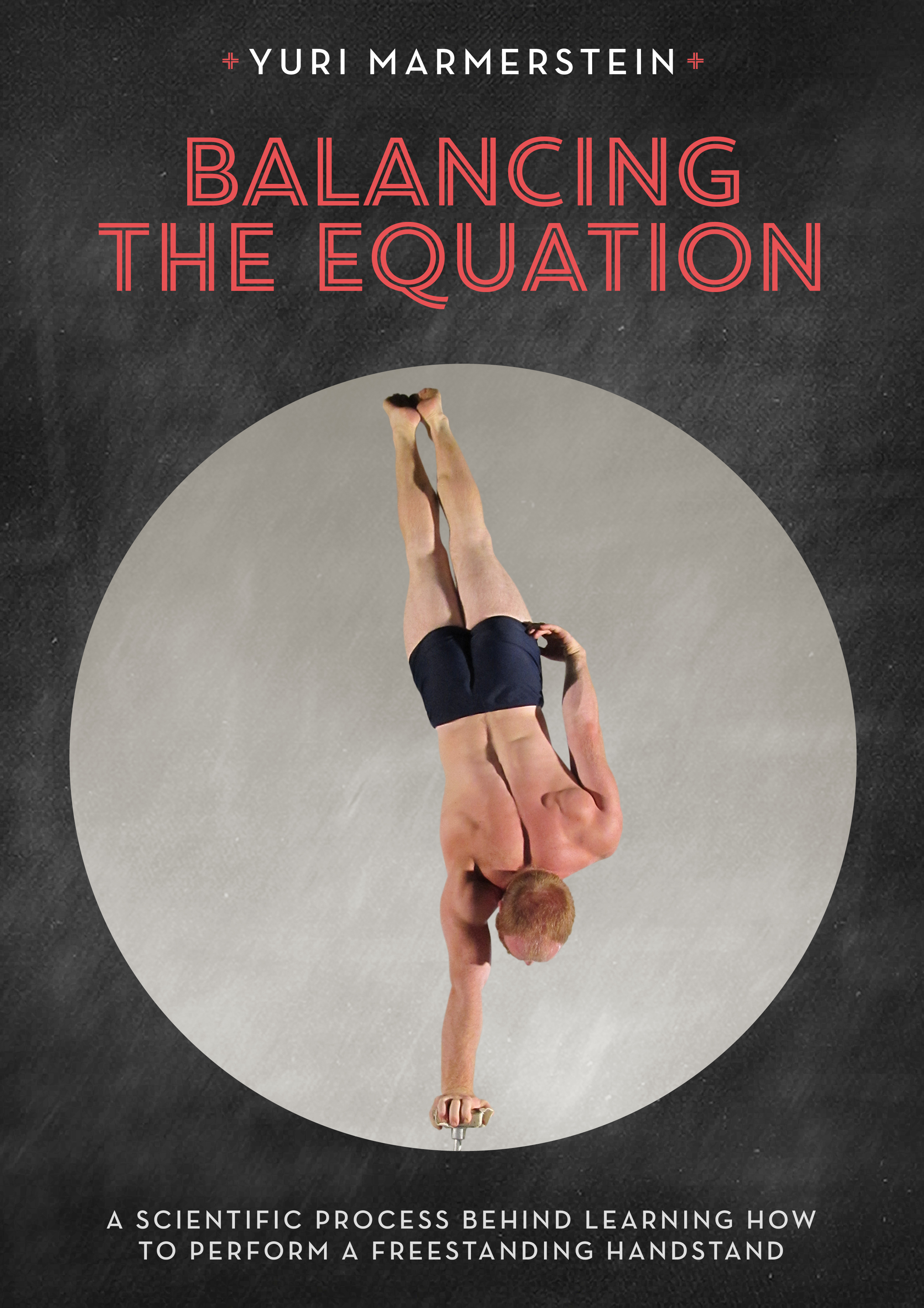

-I practice what I preach. This means that I have tried everything I recommend.

Likewise, I do all demonstrations myself rather than hire models or assistants, even if they may be prettier than me.

-I learned my skills as an adult, and I have spent a lot of time working with the adult population of various backgrounds and levels. Teaching an adult is very different to teaching an adolescent or young child and takes a unique approach.

-My format is completely open. No trade secrets or no inner circles here. I prefer to demystify this kind of training as much as possible and I will answer any question anyone asks me to the best of my ability.

Plus, pretty much everything I teach in person I've put out online for free at some point in the last few years.

-Handstands are not the end goal of what I'm trying to do. These are simple party tricks that I try to use as a tool to carry a greater purpose.

The idea is to understand the control, awareness,. and attention to detail it takes to learn these skills. This allows you to develop a greater connection to your own body, which many people in the modern world are disconnected to.

An added bonus is that it helps keep you healthy and makes you look cool.

Hopefully this post helps people to understand my background, methods and process a little better.

![IMG_2627[1].JPG](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/52912108e4b0661bae3be968/1419464011405-RXTWRPP2RDHL81AH4IDB/IMG_2627%5B1%5D.JPG)

![IMG_1928[1].JPG](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/52912108e4b0661bae3be968/1399401752869-PAVE6QMBOBEZZMTJEHOU/IMG_1928%5B1%5D.JPG)

![IMG_1351[1].PNG](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/52912108e4b0661bae3be968/1392597514440-9QRR1LKM6HTMHB3FB2FA/IMG_1351%5B1%5D.PNG)